Monday, December 22, 2008

Throwing in the towel

Monday, December 15, 2008

Just another December...

Meanwhile I'm trying to alternate between writing and preparing for job interviews. This requires preparing sample syllabi, so my desk is half buried under books: books for research, books I might use in my class next semester, books I might use in some hypothetical class I might teach in the future, books that just looked interesting. The books used to be in neat stacks, but now the stacks have collapsed into a heap.

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Footnotes

One of the things that has been fascinating about reading and editing a group of closely related papers has been observing different styles of writing and citation. I have known for years that I tend to write briefly: I usually aim for writing that is succinct and to the point, and my footnotes are accordingly brief. Some of my fellow writers in this project tend to write much, much longer footnotes. Where I write, "On X, see Author Y, Reference," they might write instead: "X is a complicated issue. For the conventional view, see author Y, whereas authors Z and W offer contrasting views that undermine the principles of Y's position." Or they might simply offer six different sources, instead of one or two. One person left me very little editing to do by meticulously casting her footnotes into the preferred format, while others required a lot more regularization.

I am not by any means saying that one of these styles is preferable to the others. It has just been interesting to get a glimpse of the various ways people work.

What's your footnoting style? Short and sweet? Long and meaty? Somewhere in between?

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

Addendum

Tuesday, December 2, 2008

This month's agenda

At any rate, these are what's currently on tap:

1) Editing a group of papers to be sent to the publisher, with an imminent deadline. I actually quite like the editing. There is something about checking other people's footnote formatting, use of commas, and the like that I find rather soothing.

2) Completing revisions on a certain article. Here the difficulty is figuring out how to respond to the reviewer's comments, some of which tack in a different direction from teh one I'm going in.

3) Surviving the semester with sanity intact. I get final papers in a couple of weeks, and I have relatively little prep to do until then. I do have a slightly sticky problem to deal with today, though.

4) Revising my book manuscript. Since I recently got a lot of thoughtful comments from two helpful readers, I need to rethink and reorganize portions of it. I'm sure I will be working out some of those ideas here, though I don't think I'll be able to get into the manuscript until January.

Thursday, November 20, 2008

Today I'm working on revisions to the liturgy article. I'm now drafted a whole new section that does a much better job of situating the community I'm talking about in the history of its order and region. So far so good. A reviewer also suggested that I need to situate the community's liturgy better in the history of its order's liturgy. That's a trickier assignment as the dating of the order's liturgy relies on arguments about the music more than the texts, and I am explicitly not dealing with the music in this article. I also am, of necessity, working from notes rather than the actual manuscripts. I'll need to take some thought about how to handle this issue.

Teaching update

After Thanksgiving they'll be doing presentations in class. Less prep for me, but still some prep; the schedule I've put together does not completely fill the class period with presentations. I'm trying to think of some short things we can do in the remaining class time: perhaps brief exercises that will be pedagogically useful, helping them prepare for their final papers, or something entertaining but also informative... I'm not averse to dismissing them early, but I'd rather not do that for all four of the class periods when they'll be doing presentations.

My spring survey course has now filled. I'll have forty students, mostly first-years, to attempt to lure into the fields of history and medieval studies. Excellent.

Friday, November 14, 2008

Helfta

As it turns out, Helfta is interestingly eclectic in its spiritual affiliations and influences. This Saxon community of nuns was founded c. 1229. According to an article I recently read in Meredith Parsons Lillich, ed., Cistercian Nuns and their World, there's a definitely-Cistercian community that served as their mother house. It's not clear to me that this was a particularly strong link, mind you. Helfta was apparently never officially incorporated into the Cistercian Order, which leads some scholars to call it simply Benedictine; yet they did adopt some Cistercian customs.

So, do they walk, talk, and act like Cistercians? Sort of. They appear to be influenced by Cistercian spirituality, as discussed in Caroline Walker Bynum, Jesus as Mother. Yet according to several authorities, their spiritual advisors in the late 13th century were Dominican and/or Franciscan, possibly out of shared interests in mysticism. They thus appear to have accepted spiritual advice from many different sources and traditions. Their institutional commitment to learning is distinctive; I suspect most women's communities following Cistercian customs did not emphasize the trivium and quadrivium to the extent that Helfta's nuns did. And the Helfta nuns develop some original and distinctive devotions, such as devotion to the Sacred Heart. Rosalynn Voaden, in an essay in Medieval women in their communities, argues that the Helfta visionaries worked closely together and influenced each other, and has an interesting discussion of the Sacred Heart.

So, to sum up, Helfta is idiosyncratic; certainly following the Benedictine rule and Cistercian observances, although not officially recognized as Cistercian. The lack of oversight from a Cistercian father abbot may in fact have been helpful to them, allowing them greater autonomy in selecting spiritual guides and forging their unique community culture.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Bits and pieces

I am paying particular attention to references to Spain, of course. There's a Navarrese community of Cistercian nuns called Tulebras which appears to have had some influence both into Aragon and into Castile, but it's difficult to find out much about it. My initial searches haven't turned up much, and the community is not usually mentioned among the standard lists of early Cistercian nunnieres (Jully, Tart, etc.). I seem to have identified yet another topic that could use more research...

Monday, November 10, 2008

Tribulations

I can teach and work on my own stuff at the same time, but I cannot teach, prepare job applications, AND work on my own stuff at the same time. And I REALLY can't do all three of those things at once and also fight off a succession of colds and aches and other nonsense, which has been the case for the last couple of weeks.

So that just makes it imperative: the remaining applications must go out this week. Preferably, tomorrow. The materials are all drafted, I just need to put on finishing touches and get them out the door. "Perfect" is becoming the enemy of "done," and I can't allow that to continue.

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

Voting medieval style

Most medieval people probably had little experience of voting, except perhaps very informally. Urban populations did sometimes have elected councils or leaders of some type, often chosen by fairly complex systems. The election system in Venice, as I recall, involved several alternations of choosing candidates by lot and then voting from among them, or voting on a pool of candidates and then choosing one of them by lot, and so forth.

Medieval nuns and other religious did have opportunities to vote. Abbots and abbesses, priors and prioresses were often elected by the monks or nuns or canons they were supposed to lead. Since they were then elected for life, individual nuns / monks / canons might not have had very many opportunities to vote in their lifetimes.

The Rule of St. Benedict says briefly that the abbot should be chosen "either by the whole community acting unanimously in the fear of God, or by some part of the community, no matter how small, which possesses sounder judgment." (RSB 64:1, in the 1982 edition from The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minn.) Unanimous choice of an abbot or abbess was probably fairly uncommon. How did this "some part of the community" method work out in practice?

In 1283 the abbess of a small Benedictine nunnery in Catalonia died. Shortly after, the prioress convened the nuns. The twenty nuns present chose three of their number as a commission and agreed to abide by their decision. They therefore acknowledged those three as possessing sound judgment and being worthy of the community's trust. All three were venerable women; two had been nuns for at least 35 years, and the remaining one had been a nun for at least 27 years. Probably all three were at least in their 40s or 50s then, and possibly were considerably older. In addition, these three nuns had an advisor: the abbot of a nearby community of Benedictine monks. These four people deliberated for a time--not more than a few hours, in this case--and then announced their decision. They chose as the new abbess the community's prioress, a woman who had held the offices of prioress and infirmarian in the nunnery for 20 years. They praised her learning, prudence, and discretion, and their choice was attested by all those present. The witnesses included not just the twenty nuns of the community, but also its chaplain as well as representatives from the local cathedral and other men's communities.

This election went very smoothly: a well-qualified candidate was available and the chosen delegation came to agreement quite easily. Certainly not all medieval religious elections went so well, but this example must be practically the ideal.

Incidentally, the Catalan scholar Ramon Llull seems to have been interested in voting (among his many other interests) and proposed some much more elaborate schemes for conducting elections; I found some discussion of this methods here.

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Planning a medieval survey

The spring course is a survey of medieval history from 1000 to 1500. I've taught the medieval survey before, but with a slightly different time frame. I've also been asked to address the Italian Renaissance to some extent, since that isn't being covered by other history courses here this year. I haven't taught the Renaissance in any depth for a while, but since I'm going to do it here, I also think we will discuss the question of the 12th-century renaissance.

I am undecided on using a textbook; I usually use Barbara Rosenwein, Short History of the Middle Ages, but have ordered some others to look over, too.

I will probably use Geary, Readings in Medieval History as a general reader, but am open to other suggestions.

Other primary sources I expect to use:

some of Chretien de Troyes (I particularly like Yvain)

Letters of Abelard and Heloise

Dante, Purgatorio

Beyond that I have a long list of stuff I'm considering, including far too many ideas. So some questions for any readers lurking out there:

Textbook: yea or nay? if yea, any suggestions?

Is there a source collection you prefer to Geary?

Other standalone primary sources you'd consider especially important to a survey that runs from 1000 to 1500?

Any primary or short secondary works that are particularly good for the Italian Renaissance or the 15th century?

Thursday, October 23, 2008

Medieval history at the AHA

I just got the AHA annual meeting schedule in the mail today. Usually there's something of a dearth of medieval sessions at the AHA--actually, even if you put together the ancient, medieval, and early modern sessions, they are probably still outnumbered by sessions on, say, the U.S. since the 1960s.

This year appears different, though; so thanks to the Program Committee and the session organizers for having a diverse lot of medieval sessions. Some of them do come from the affiliated societies--the American Society of Church History and the American Catholic Historical Association can usually be relied on for a few medieval topics, and societies focused on regions like Spain or Italy often have a few as well. Although I still observe the scheduling problem of sticking several of the medieval sessions in the same time slot, at least this year we are not in the position of seeing the only 3 or 4 medieval sessions all in the same slot.

Here's what I noticed on a quick spin through the catalog (apologies to any sessions I've missed):

- Reform and Clerical Culture in the Eleventh Century (Fri. 1pm)

- Identities: Forms and Functions in the Middle Ages (Fri. 3:30pm)

- Medieval History: Old and New Classics III (Fri. 3:30pm)

- Late Medieval and Early Modern Catholic Responses to Heretical "saints" (Fri. 3:30pm)

- New Directions in Morisco Studies (Fri. 3:30pm)

- Greek History and Its Islamic Fate, 630-930CE (Sat. 9:30am)

- Problematic Passions: Case Studies in the History of Emotion in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Sat. 9:30am)

- Women and Community in the Middle Ages (Sat. 9:30am) (this looks particularly nunnish, so I will do my best to attend)

- Christianity, the Religious Other, and Demonic Language in Medieval and Early Modern France (Sat. 9:30am)

- Cultural and Intellectual Responses to the Crusades (Sat. 2:30pm)

- New Trends in Medieval Spanish History (Sat. 2:30pm)

- Locating Jews in Medieval Iberia (Sun. 9am)

- Reassessing Reform: Medieval Models of Change (Sun. 9am)

- National History in an Age of Globalization: The Case of Medieval France (Sun. 2:30pm)--especially notable for the participation of Dominique Iogna-Prat)

- Bound Feet, Corseted Waists, and Veiled Heads; Chastity Belts and the Tropes of Contained Femininity (Sun. 2:30pm)--ok, this one is only sort of medieval; it does feature Albrecht Classen on chastity belts and looks potentially quite interesting

- The Other Middle Ages: New Developments in Byzantine Studies (Mon. 8:30am)

- The Papacy: Its Friends and Foes in the Later Middle Ages (Mon. 8:30am)

Having written all that up, I'm pretty impressed with the collection: a good variety of topics and regions. There is certainly some medieval stuff hiding in some of the thematic sessions, and there are also a good number of early modern sessions (and a few ancient ones) that I haven't listed here. The concentrations at Friday 3:30 and Saturday 9:30 are unfortunate, but the AHA only schedules two sessions a day, so some kind of logjam was inevitable with this many sessions. Medievalists attending the AHA should have plenty to interest them.

Monday, October 20, 2008

Last Monday was a "fall break" day off for me--my institution doesn't have a full week of fall break. That one disruption totally threw me off the weekly routine; I kept staying up too late during the long weekend, and so spent last week feeling groggy, out of sync, and vaguely cross. And I got very little done. I think I've finally reset to normal.

Sometimes a break comes at just the right time, and for me this one seems to have come at the wrong time.

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Other last nuns

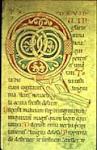

First I'm going to link to Jonathan Jarrett's post on the last nuns of Sant Joan de Ripoll, aka Sant Joan de les Abadesses. Go read it; click on the charter and enjoy the lovely script and the impressive collection of signa.

The ousting of the nuns from Sant Joan has always seemed fishy; the counts levelling the accusations against them benefit so clearly that one becomes skeptical. The former abbess Ingilberga, I believe, ended up buried at the altar of St. John in the cathedral of Vic, although I can no longer recall where I read that. It seems a final sign of devotion to her community's saintly patron.

Sant Joan was far from the only nunnery in the Middle Ages to be forcibly closed. Here is one of those cases where I'm sure Jo Ann McNamara's Sisters in Arms describes some other examples, but the lack of a subject index makes it exceedingly difficult to find where. However, my own notes on other houses in Catalonia turns up several others, all from the later Middle Ages.

One house of Hospitaler women, which had only been opened a few years earlier, closed in 1250. Seven women's communities in Catalonia closed between 1307 and 1399; another fourteen closed between 1407 and 1475. There's another group of twelve or so closures in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Why? For many of these I've found very little information so far. Unlike the nuns of Sant Joan, the nuns of these houses were not accused of parricide, and not explicitly called whores either. Where rationales for the houses' closing can be found, the reasons cited are poverty, disrepair, and dwindling numbers that made it difficult or impossible to maintain the monastic rule. Josep Marques discussed seven of them in an article for Estudis del Baix-Emporda 15 (1996). All seven of these houses were small, with relatively few nuns (seven or eight, often becoming fewer over time) and modest endowments. One house was closed when its membership came to consist of the prioress, a single nun, and a servant; another was built in a location prone to flooding. In most cases the remaining nuns joined another community, and the properties and title of prioress would be attached to the other community as well.

Several of the 15th-century closures were Cistercian; these were usually ordered to close by a superior Cistercian abbot, on the grounds that they were too small. In these cases what tended to happen was that the remaining nuns joined a larger Cistercian nunnery, while the property went to Poblet, the large Cistercian men's monastery in Catalonia. That seems a bit hard on the women's communities, who had to take in extra membership without getting extra resources to support them. These closings may be part of a larger pattern of similar phenomena in the 15th century.

In a lot of cases, however, we just don't know what the rationales were. Nor do we know whether there was truth to the reasons claimed, or whether a group of perfectly ordinary nuns fell victim to political and ecclesiastical machinations.

Tuesday, October 7, 2008

Notes from Crown and Veil, 1

I admit that art history is one of my weak points. Certainly I am just as capable of admiring a pretty image as nearly anyone, and I can differentiate between Romanesque and Gothic to some extent, but my knowledge of art history is not that deep.

So this volume's focus on art history is a welcome corrective for me, providing a different point of view and things to think about. And it has pretty images, too.

Three of the essays in Crown and Veil really focus on the visual: Jeffrey Hamburger and Robert Suckale give a general introduction to the art of religious women, Carola Jaggi and Uwe Lobbedey deal with architecture, and Barbara Newman discusses women's "visual worlds."

Hamburger and Suckale give what seems to be a good overview of what is known about women's art in the Middle Ages, with some interest in reconstructing how works of art were used within the cloister. This sort of reconstruction of the material world of a monastery is immensely useful, I find; it helps give a real sense of what monastic life was like. They devote attention to textiles as well as sculpture and painting, and discuss monastic works of art as functional rather than merely decorative, serving a variety of practical and devotional purposes within the community. Very different from encountering the art in museums, moved far out of its original context.

Jaggi and Lobbedey's essay on architecture emphasizes diversity: although there appear to be general patterns in the layout of many monasteries, they cite many variations, most based on the local conditions of each community. This fits in with ideas I've encountered elsewhere, that communities of nuns were often idiosyncratic and relied heavily on local founders and supporters. Some of their comments provoke further questions. For example, they mention the grille as a popular measure of enclosure in German houses of Dominican nuns. I don't entirely know when this feature originated and how/when/where it spread, though. As I recall, in the 15th century a lot of Spanish nunneries had grilles installed--so they didn't have them before--yet the German Dominican houses have them in the 13th century. An interesting question, I need to see if anyone has really looked at this.

Finally, Newman emphasizes a special connection between women and images, looking both at visionary nuns and at guidance for nuns that emphasized visualization as part of prayer. In some ways this essay reads like a boiled-down version of work she's done elsewhere (her extensive work on Hildegard of Bingen, for example), but it's a nice summary of some of her points.

Saturday, October 4, 2008

Getting behind

Well, as I said, it was a busy week, with a lot of things to do.

Which is why it was a particularly bad time to come down with some miscellaneous malaise. Now I'm behind on everything. I'll be back once I dig myself out from under the piles of essays, books, and chores.

Tuesday, September 30, 2008

Crown and veil

Busy week ahead: the first batch of essays is in to grade, I need to finish revisions to an article imminently, and that ms. I agreed to review is due soon. Let's not even talk about job applications yet.

I also still have a large stack of books to peruse, and today I looked at Crown and Veil, edited by Jeffrey Hamburger & Susan Marti. This is a collection of essays on female monasticism intended to accompany an exhibition of artwork from women's monasteries in Germany. From my cursory overview so far, it's a good look at the state of the subject. While it focuses geographically on Germany, Hamburger's introduction discusses the need to balance examining what is distinctive about female monasticism with how it fits into, and in turn changes, the larger world of medieval church and society. Hm, now there's a familiar theme. The collection then kicks off with two essays surveying the history of foundations, orders, and so forth, and goes on to examine numerous topics, including architecture, artwork, liturgy, patronage, and economy of women's monasteries. I plan to discuss some of these essays at greater length as I find time.

Friday, September 26, 2008

Insularity

I want to follow up on the end of yesterday's post and the comments. I find that working on medieval Catalonia can be a weirdly disconnected experience, because Catalan scholarship and international scholarship often have little to do with each other.

As Notorious says of Catalan scholars: "they know their local sources inside and out, and tracking down their footnotes is almost always rewarding." Yes, exactly. But the stuff I read regularly is not much concerned with theoretical frameworks, just as she said. In particular, I see only a few Catalan scholars who pay much attention to gender. That is partly a reflection of the sort of thing I read. Since I'm working on monasticism, I read a lot of things concerned with the institutional history of regional monasteries, or a sort of antiquarian exploration of some local monastic community. This is all useful for me, but I have to do most of the work of relating it to studies of monastic life, patronage, etc. in other parts of Europe myself.

Jonathan Jarrett points out: "for the scholars I read from Catalonia theoretical debates do exist, they just tend not to be the same ones that we worry about. Depending on the scholar, the debate is either with the Castilians or with the French, and often enlisting one against the other." True. I find that at times, too, but I think that's far more true of work on earlier periods--up to 1100 or so--than on the later Middle Ages.

The disconnection goes both ways, though. If Catalan scholars focus on local materials and debates, there are surely good reasons for that; since I often read older (1960s and 70s-era) scholarship, I'm sure there were political reasons for that, too. But among the English and North American authors I read, Catalonia (in fact the whole crown of Aragon) is virtually ignored. The exception is the "feudal transformation" period that Jonathan has been discussing at length. There Catalonia is seen as an interesting case study and discussed in a number of general works. For later periods the relationships among Aragon's three religious cultures are extensively studied, but beyond that few references to anything regarding eastern Spain seem to reach general scholarship. Despite the efforts of recent textbooks, such as Barbara Rosenwein's, to include many regions and cultures, I still get a sense that, for most scholars, France and England are seen as normative, while Spain is strange and exceptional. But even within Spain, clearly Castile is the best exemplar of that exceptionalism, so Catalonia-Aragon can be neglected.

There are in fact quite a few specialists on Catalonia, Aragon, and Valencia working in North America. But the region still doesn't seem to be well integrated into most scholars' general understanding of the Middle Ages.

Thursday, September 25, 2008

Cistercian nuns in Catalonia

I've been dabbling the last few days in scholarship on Cistercian nuns, particularly on the topic of whether there were Cistercian nuns. Well, yes, there were, but the question is when they were, and how nuns became attached to the order.

The traditional narrative holds that the early Cistercians distanced themselves from women, except for a few leaders such as Stephen Harding and Bernard of Clairvaux who offered spiritual advice to religious women only informally. Then in the late 12th century, the clamor of women seeking places in monasteries, combined with other pressure, forced the Cistercian General Chapter reluctantly to admit houses of women to the order.

Probably the primary voice arguing against this narrative in Constance Berman's. In "Were There Twelfth-Century Cistercian Nuns?" (Church History 68:4, Dec. 1999, pp. 824-864) she attacks the question head-on, and connects it to her larger attacks on the traditional narrative of Cistercian origins found in The Cistercian Evolution. Berman's position is that the 12th-century expansion of the Cistercian order happened through groups of reforming hermits & monastics taking up Cistercian customs, and gradually being incorporated into the developing order (rather than new houses being seeded, so to speak, directly from Citeaux and Clairvaux). She further argues that many of these reforming groups included women, that such women viewed themselves as Cistercians, and that historians have applied overly rigid and anachronistic standards to dismiss many women's houses as only "imitating" Cistercians. She generally argues that, where local records of a house having Cistercian customs conflict with the order's narrative sources, the local records should be trusted, because she considers the dating of the narratives to be highly questionable.

Now, Berman has her share of critics on these issues, but the material I am looking at inclines me toward her approach. I'm looking at material related to a Catalan nunnery (Santa Maria de Vallbona) which is presented as unambiguously Cistercian in the local historiography. Catalan historians often seem to blithely ignore historiographical debates focused on other regions--in fact no Catalan article related to Vallbona appears to cite any of this controversy, or the traditional narrative. But they do know their local sources quite well. In fact, the foundation story that appears in the multiple histories of Vallbona I've looked at fits Berman's pattern beautifully:

A charismatic hermit called Ramon settled down in the Good Valley of Vallbona, attracting a number of followers, both male and female. After some time the group decided to adopt a more formal set of customs and separated, the men perhaps joining the community of Poblet. The women invited a nun from the Navarrese Cistercian community of Tulebras to come and bring them Cistercian customs, which she did c. 1175. That is not super-early in the Cistercian chronology, but it is earlier than when the General Chapter is supposed to have been pressured to admit women. It's a little earlier than the foundation of Las Huelgas in Castile. I do think, based on the local accounts and sources, that Vallbona was Cistercian. Its material seems unfairly obscure, though; it's seldom cited in studies of Las Huelgas, much less related to developments in France. Unfortunate, as it could provide useful counterpoint.

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

Catching up

Well, I am not sure what happened last week. It's only in the second week of the semester here, but somehow I found myself very preoccupied with classes and short on sleep. I seem to have rectified that situation to some extent now.

Meanwhile, I am plugging away revising a conference paper (project A). I am finding it a bit recalcitrant, possibly because I'm more interested in other things (projects B and C), but A has a more imminent deadline. I've just downloaded or requested a blizzard of books and articles for project B, which I'll start reading as I finish the work on project A. As usual, combing the indexes of journals has flushed out several articles which I really should have read already, or at least been aware of. That does tend to induce some guilt, but at least I'm aware of them now...

Thursday, September 11, 2008

Tuesday, September 9, 2008

The Great Divide

I recently read an article on the enclosure of nuns that illustrates some of the interesting questions around this issue, as well as some of my ongoing frustrations with scholarship on women and religion. I happened on the article somewhat by chance--it's in a collection of essays that caught my eye while I was looking for something else on the shelf. I'm glad I found it, though.

The article is Francesca Medioli, "An unequal law: the enforcement of clausura before and after the Council of Trent," in Christine Meek, ed. Women in Renaissance and Early Modern Europe (Four Courts Press, 2000). The title of the essay collections is indicative of my current complaint. Since these essays focus on Renaissance / early modern women, I hadn't previously encountered it in reading scholarship on medieval women. In short, medievalists and early modernists don't talk to each other enough. Medioli's essay further illustrates the problem. She's interested in ideas of enclosure before and after the mid-1500s Council of Trent, and she discusses some monastic rules dating from before Trent, but she doesn't deal to any significant extent with any of the scholarship on enclosure in the Middle Ages.

This problem comes up again and again in my reading on monasticism. Medievalists pick an ending date--for historians of Spain, often 1492, for historians of England, often the Dissolution of the early 1500s--and stop there. Early modernists pick a start date, usually in the 1500s, sometimes in the late 1400s, and start there. It's rare for a historian on either side of the medieval / early modern divide to engage systematically with work done on the other side.

Yet, for women religious, there is a lot of consistency crossing that line. Similar rules, customs, and preoccupations dominate the theory and practice of women's monastic lives both before and after 1500. The Council of Trent is in some ways a watershed. But, as Medioli points out, it's a watershed of enforcement, not of ideology. In the years after Trent, the enforcement of enclosure rules became much more stringent and effective, but the basic principle of enclosure had been established by Boniface VIII's bull Periculoso in 1298 and discussed more generally long before that. Medioli's discussion of the Trent materials, particularly the differences between the draft and final versions of the relevant constitutions, is quite interesting. Yet I found myself frustrated that the scholarship on earlier norms of enclosure was not more fully addressed, and also frustrated that there was little discussion of customary practices within nunneries. We know from many anecdotes that many nunneries did not observe enclosure very strictly, but we don't necessarily know whether these nuns were working under consistent customs that just happened to be looser than the ideal, or whether there was in fact an "anything goes" mentality. And just how was it that church leaders managed to enforce enclosure more effectively after Trent, when the ideal of enclosure for nuns had already existed for centuries? Or did they succeed only in Italy (Medioli's focus)? There are some very important questions here which really require an approach that spans medieval and early modern.

R & R

Alas, not the fun rest and recreation kind. I recently got an article back with a revise-and-resubmit recommendation.

I've often seen people complain about their readers' reports that it seems the readers hardly read the work, or at least wanted something very different. That's not the case here. Both of the reports are encouraging, and both offer concrete suggestions for improvement. And I think both reports are fair: these are indeed areas that need improvement.

One report will be fairly easy to address, I hope. The other will require some digging in the library and reconceptualization. What concerns me here, actually, is that the second report has two layers of comments. One layer requires putting my piece into dialogue with some a particular set of scholarship, which I think is manageable and a reasonable goal. The other layer may require a much more involved revision, perhaps even reconceptualization, of the project. I don't know that I can do that, at least not quickly, as it would require examining original manuscripts which I don't have. But, I'll see what I can do.

Monday, September 8, 2008

First day

I need to adjust to the new rhythm of the school year: two days a week teaching and being on campus all day, three days working in the home office on research, writing, and the rest of it. I hope to confine teaching responsibilities to my two teaching days as much as possible. I have a lot of writing to do, and it is too easy to let teaching fill all possible time.

Monday, September 1, 2008

A return to nuns

The last few entries, I note, have concentrated on matters personal-professional. They've brought a few new commenters out of the woodwork--welcome! and thanks for reading!

But now how about some nuns? Here's an anecdote I encountered in my research some time ago:

Once upon a time a young lady named Geralda wished to enter a particular nunnery. Now, there are some questions we can't answer here: for one thing, we can't be completely certain whether Geralda herself had a burning desire for the monastic life, or whether her parents thought the monastery would be the best place for her. She and her family were noble, but not titled nobility: her father likely held a castle or two in the countryside.

Regardless of whose idea it was, she was certainly a socially acceptable candidate, and the nunnery she sought to enter was eminently respectable: a few hundred years old, well established, regularly accepting young women from the area. They claimed, however, that they could not take Geralda. They were too poor, they said, and could not possibly support another nun. It was expensive, after all, to take in a young woman and provide her with food, clothing, and so forth for her entire life.

Geralda's father may not have been count of anything, but he apparently had some pull somewhere, because Geralda and her family filed complaints all the way up to the pope. Having been turned away from one nunnery, it might have been sensible to seek entrance into another. But for Geralda and her family, apparently only this nunnery would do. Why? This is another point on which we don't have much information. This particular nunnery was not too far away from the family's residence, for one thing; trying to enter another nunnery would probably require her either to join a much smaller community, or to join a community much farther from home. Or maybe Geralda was particularly fond of the saint that this nunnery was dedicated to. Or maybe she had an aunt already a nun there, although if that were so, it ought to have been easier for her to be accepted there.

Now, the pope was a busy man, and not about to trek down from Avignon himself to investigate, but he did appoint a delegate to look into the matter. Before the delegate, Geralda presented her complaints, and the nunnery in turn sent an official who laid out all the debts and other difficulties that made it just impossible, sorry, for them to take in another nun. And the delegate agreed with the nuns' official. And that should have been the end of it.

But it clearly was not. Because, lo and behold, some years later Geralda shows up in the list of nuns signing on to a charter at that nunnery, so clearly they had let her in after all. One suspects that she and her father had been induced to make some sizable donation to the community, to make up for the terrible expense of her upkeep. Yet, evidently, a happy ending for Geralda, who had fought hard to be admitted to the monastery of her choice. One hopes she lived a long and contented life there.

Friday, August 29, 2008

Taking stock

This has been a busy week. There was a parental visit and a full-day new faculty orientation on top of the various other stuff I regularly do.

The start of the semester seems more real now due to the orientation. I staggered home from it with my brain full of information and a tote bag jammed full of event schedules, contact information for student and faculty support services, pamphlets on writing and grading, etc. I've also acquired keys to my new office and verified that the bookstore has my books in. Today I finished up my syllabus. So I'm just about ready to go with classes, and I still have a full week to plan class before I need to teach.

I need to not let teaching swamp the writing and other aspects of my professional life, though. Therefore, I'm going to take stock of my summer accomplishments as well as goals for the fall.

This summer I did the following:

- finished a conference paper

- participated in a very lively conference session

- agreed to co-edit a project which should see print in the spring

- finished and submitted an article (entirely separate from the conference)

- began revisions on the conference paper

- began to think about the paper I'll write after that

- read assorted & sundry volumes

- planned my fall course

This fall I'll need to do the following:

- review a manuscript, as recently requested to do

- finish revisions on the conference paper

- do my responsibilities as co-editor

- submit an abstract for Kalamazoo and work on the ensuing paper

- apply for jobs (I may submit as few as two applications)

- teach my fall course

That all sounds reasonably manageable. The hitch is I have two projects out and under submission, and if they come back with revision requests and short deadlines, things could get much more complicated. As things currently stand, I can be satisfied with my summer and optimistic about the next 3 months.

Monday, August 25, 2008

Out of step

All around the blogosphere, people are teaching their first classes or stressing about doing the same. I'm somewhat embarrassed to admit that I have a ridiculously long time before the same stresses kick in. At the college where I'll be starting work this fall, classes begin next Thursday (schools typically begin after Labor Day around here). Since the class I teach is Mon.-Wed., I won't actually step into the classroom until the following Monday, two weeks from today. I do have things to take care of this week: I need to stop at the bookstore and make sure the books are in, I need to pick up the keys to my new office and move stuff into it, I have a new faculty orientation to attend this Thursday. But I feel a little removed from the start-of-semester hustle and bustle. This week I'll take care of those chores, and try to finish off some things from my summer to-do list. Next week, I suspect, I'll start feeling more excited about teaching classes again.

Friday, August 22, 2008

A curious development

Today I received a request to do a manuscript review. For an actual journal, not for a friend.

This has never happened before, and I am not sure why it has happened now. The topic of the article is within my broad field, but does not appear to be in my specialization, so I'm unsure why my name would have floated up as a reviewer. Further, I got the message at my newest email account, the one I have through my new employer. I've had this account all of six weeks or so, and not very many people have the address. Now, my graduate advisor is one of them, so it's possible he suggested me.

I'm trying to decide whether to agree to do the review. It will need to be done within the next couple of months. As I look ahead, I'm conscious of a number of important chores for September and October. I'm not sure how long this will take; it is only an article review, not a whole book, so it really seems as though I ought to be able to critique it in a day or two of work...?

It is still startling, though, to be viewed as a person appropriate to review someone else's work.

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

Revision, again

I made a slew of revisions to the liturgy article today, based on comments from a helpful reader. (Thanks!) I hope this will clarify the argument considerably and also explain the specialized vocabulary better. Unfortunately it has probably also gotten longer.

Helpful Reader also returned comments on the patronage piece, which I haven't gotten to yet, and remarked that it seemed more mature. I found this curious, since the patronage piece was dashed off in a shortish period of time--no more than six weeks, I'd guess, and probably less--before a conference, whereas I've been laboring over the liturgy article for much longer. On and off for two years, in fact.

It's occurred to me that perhaps that on-and-off process has not helped that particular paper. In revising it I've had to cut repetition regularly, probably due to writing sections at different times. I've had to make the argument come through more clearly, perhaps because I've grown too close to it and have more trouble expressing it clearly. Perhaps I need to try harder to finish a piece of writing in a short period of time, rather than writing one section, coming back a few months later and writing another, etc.

Readers, feel free to chime in: how to you do your most effective writing? Do you try to finish a draft as quickly as possible, or come back and add to it at intervals, or something else?

Thursday, August 14, 2008

Reading for inspiration 3: From Heaven to Earth

Some books make my brain practically spark with thought. Teofilo Ruiz's From Heaven to Earth is one of them.

I put this book into my stack of things to reread for this project because its discussion of changing Castilian mentalities deals with some similar subjects: property, inheritance, wills, giving of various kinds. In addition, its focus on Castile suggests fruitful comparison with other Iberian regions. Today I went back through the book, and felt well rewarded. Ruiz's argument is complex and difficult to summarize, although the book is short. It comes down to: the 12th-13th centuries in Castile saw major shifts in attitudes about property, sin, and intercession, as people moved from an otherworldly-focused approach to a more down-to-earth practical style. Whereas earlier testators tended to entrust clergy with undifferentiated gifts, he argues, later testators divided up their legacies, using combinations of small gifts, which they expected to be spent for specific purposes. He suggests that charitable giving in particular tends to be performative: money left for clothing 12 honest paupers, for example, is symbolic and ceremonial, related to the donor's ideas about charity and poverty more than about the real needs of the poor.

Since I'm looking at later material, my testators are past this transition, but this is exactly the kind of pattern I'm seeing in 13th- and 14th-century wills and other donations. I'm seeing several variations on the pattern, however, which gives me something to talk about.

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

Sisters in Arms

By popular request, I'm now commenting on Jo Ann McNamara's Sisters in Arms. Well, OK, not exactly by popular request--but Notorious put in a request, so that's one. I do try to please my public, small though it be.

Now over ten years old, this is still an impressive book, and an essential resource for those interested in women's monasticism, not just in the Middle Ages, but from the origins of Christianity right down to the present. Its great strength is McNamara's ability to synthesize a great mass of scholarship on religious women, on extremely diverse periods, and make a coherent whole out of it. One of its major flaws is the flip side of that: because McNamara is wielding a quite broad brush, at times the book sweeps over variation in a given period.

The other major flaw is the index. It's simply not helpful. Someone apparently decided that this book only needed an index of personal and place names. There is, therefore, no thematic index at all: if you would like to see where McNamara discusses her favorite theme of syneisactism (roughly, partnership between religious men and religious women), or reform, or sexuality, or virginity, or charity, or...well, you get the idea. There is no index to help you, you will simply have to hunt through this massive tome yourself. I've spent more time than I can count riffling through the book, muttering, "I could have sworn she talks about authority and disobedience in here somewhere...maybe it was this other chapter...no, that's much too late..." etc.

Lacking time to reread the entire book, I concentrated on ch. 9-13, which cover the high Middle Ages (roughly, 1100-1400, here). These five chapters give an excellent overview of issues in women's monasticism during this period, but don't address my current preoccupations (benefaction and patronage) to any significant degree. McNamara notes women flocking to join charismatic preachers like Robert of Arbrissel, attempting to affiliate with the Cistercians, forming informal beguine houses, and so forth, but offers few comments on the lay supporters of such houses. There is, nonetheless, excellent stuff here: the dominant theme is the male clerical hierarchy's desire to separate itself from religious women, while simultaneously regulating the behavior of the women. One of the chapters is a good discussion of the financial burdens of women's monasteries, another is a fine introduction to female mysticism in the period, and yet another addresses damaging preoccupations with the sexuality of enclosed women (among historians as well as medieval churchmen).

In short, I remain impressed with McNamara's accomplishment here. It is hard to imagine a more thorough summation and synthesis of scholarship on religious women, c. 1996. A revised and updated version would look rather different, since the book has itself helped to establish paths for research in the intervening years. I only wish it were easier to make use of its wealth of information.

Friday, August 8, 2008

Reading for inspiration, 2

If it had been a while since I'd read Rosenwein, it has been even longer since I read Lester Little's Religious Poverty and the Profit Economy. I seem to recall reading it for my exams in 1999. Although I hadn't read it since then, its argument has definitely stayed with me and had a formative role on my thinking about late medieval religion. His basic narrative of the rise of the mendicant orders is definitely something I've internalized.

In tracing the development of anxieties about money and new forms of urban religious culture, Little's work here bridges the chronological gap between Rosenwein's 11th-century monastery and my 14th-century monasteries. In Little's discussion of religous culture, however, he deals in turn with: 1) traditional Benedictine monasteries, notably Cluny; 2) reformed monastic orders such as the Cistercians and Premonstratensians; and 3) the mendicant orders (Dominicans and Franciscans). Each group gets their turn, and then ceases to be discussed further.

The communities I'm dealing with in this paper, however, are Benedictine communities that have survived, and even flourished, despite the arrival of Dominicans and Franciscans in droves. The fact that lay people in an urban environment still supported old-fahioned Benedictine nuns at the same time as they supported mendicant orders, and the poor generally, is one of the themes I'm attempting to deal with in this paper. I'm looking at nuts-and-bolts sorts of issues, looking at everyday acts of support for various causes, which Little's work of synthesis doesn't really address.

I would note, also, that Religious Poverty doesn't deal very much with women. There is some discussion of the beguines and of St. Clare as a follower of St. Francis. Women belonging to Benedictine, Cistercian, etc. communities don't really appear here. I think the traditional assumption was that women's communities of such orders operated much like men's communities of the same orders, although more recent work in the field tends to argue that women's houses filled different social and spiritual roles than men's houses.

None of these remarks should be considered major criticism of Lester Little; I respect very much what this book does, even though it doesn't answer all my questions. Which is good, after all, because if the questions were already answered I'd have nothing to write.

Wednesday, August 6, 2008

Reading for inspiration

The first of the new stack I've tackled is Barbara Rosenwein's To Be the Neighbor of St. Peter. I'd already read it, but a commenter's recommendation last week reminded me that it might be worth another look.

Rosenwein emphasizes that the meaning of acts may change even though the forms (such as gifts, sales, etc.) remain the same. This point could serve as a caution against finding parallels between the phenomena she describes and other societies and periods--yet I certainly see a lot of common elements which I think I could meaningfully draw on.

Differences: Rosenwein and I are looking at different regions and, perhaps even more importantly, different periods (she at the 10th and 11th centuries, I at the 13th and 14th). I am looking primarily at women, not at all donors; the female donors and testators I'm looking at lived under a different legal and institutional framework than the men and women of 10th-century Cluny.

But Rosenwein's major themes deal with how gifts and exchanges of property create and reinforce bonds between Cluny and its donors. Those sorts of social relationships seem to me to also exist in the later period, and to be of importance in determining who gives gifts to institutions and why.

Tuesday, August 5, 2008

Proceeding slowly

Monday, July 28, 2008

Were donations always worth while?

Late medieval monasteries got a lot of donations, and often they were quite specific. I often wonder how welcome some of these gifts really were.

For example, people might choose to make a substantial gift of property or rents to a nunnery, and dedicate those funds to the support of a particular priest, who is to offer masses at a certain altar in the community at specified times of the year. Do the nuns actually welcome this? What exactly do they get out of it, hmm? They have more opportunities to attend mass, although they probably had plenty of such opportunities. They get another priest visiting the cloister. They probably get a bit of extra food or money on the anniversary of the donor's death. Wouldn't many communities prefer funds given to buy clothing or food, or funds given with no particular purpose, that they could use as they chose? This kind of gift strikes me as being more about the donor's wishes than the recipients'. If the donor is sufficiently wealthy or powerful, though, I'm sure the community accepts the gift cheerfully to preserve good relations.

In one of my documents, a widow gives all her property to a community of nuns, in exchange for food and clothing during her lifetime. Mutual benefits: the widow, perhaps aging or ill, now has secured basic care for herself, while the nuns hope to enjoy the income of the property in the future. The donation happens in 1308; the parcel pops up several times in later documents. First (1309) the nuns have to enter litigation to secure their claim to the property. In 1310 they find a tenant for it, who takes it for a 3-year contract. Normally the nuns would prefer to have a "solid" tenant, someone who does homage and is bound to the land perpetually, but they apparently haven't found anyone willing to make such an arrangement. In 1312, the tenant gives it back. In 1314 the nuns find a new tenant for the property, again someone not willing to do homage for the land. This one is willing to pay a large fee for the privilege of not doing homage, though, so that's something. So this is a gift that entailed potentially costly litigation, and may have sat vacant and uncultivated from 1308 to 1310 and from 1312 to 1314; all in all, it seems a rather troublesome gift. Perhaps its real value is that, when she gave it, the donor also forgave a debt which the abbess owed her.

Maintaining good relations with one's creditors: Priceless.

Next item?

OK. Liturgy article is revised and off to a friend for reading. (Thanks, friend!) What's next?

There are two pieces I'm particularly interested in working on: one about nuns and slavery, and the other about patronage of and donations to nunneries. For the first I'm just collecting bibliography and sources right now, as the second must take priority. It's already committed and needs some revision by October. The amount of time I have to work on it will also drop sharply in September once I start teaching, so I'd like to get the bulk of revisions on it done by the end of August.

Most of my research focuses directly on nuns themselves: what they did, how they lived, how they handled certain obstacles and situations, and so forth. This piece still uses monastic sources, but focuses on a different subject: the lay women who supported nunneries. There were a lot of them. I'm firmly convinced that successful late medieval monasteries really had to have a lot of small-to-middling donors to keep them going. Large donors were nice, too, of course, but the very wealthy might prefer something splashy like founding a new monastery. In the sources I'm working with I'm seeing a lot more smaller donors. Why did they give to nunneries? Did they get some benefit, social, spiritual, or otherwise, from doing so? How did miscellaneous small donations affect the communities which received them? These are the sorts of questions I'm approaching here.

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

When the writing is not good

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

But what did other nuns read?

What about nuns on the continent? As far as I know there is no comparable study and book-list for any region. Alison Beach has done some work on women and book production in Germany (more for the to-read list), and there are several other scholars who have worked on nuns' writing and artistic production there. Fiona Griffiths' book on Herrad of Hohenburg makes a case for a high level of literacy, indeed of theological sophistication, on the part of Herrad, and perhaps others of her nuns. This case might be quite exceptional, however. The various nuns and communities which produced spiritual treatises (such as Helfta), may also be quite exceptional. So, some communities might be especially noted for learning: what about other houses, especially smaller and poorer ones?

Any monastery had to have some books. In the first place, a monastery required books to perform the liturgy. Bell notes that over half of the surviving manuscripts of English nunneries were liturgical. One might expect similar figures for medieval survivals elsewhere. Except that in Catholic Europe, the liturgy was substantially revised by the Council of Trent in the mid-16th century. Older books were in many cases discarded as the new ones came in, especially older books that had no particular artistic merit and therefore didn't seem worth keeping. Thrifty religious sometimes recycled such outmoded books as end-papers for new ones.

In the second place, a community following the Benedictine rule was supposed to distribute one book annually to each member, and this was to be read over by the nun or monk during the year and then returned. By this logic, even a small house ought to have at least as many non-liturgical books as it had members.

For the Iberian kingdoms there seems to be not much known about writing, literacy, or book ownership among nuns at any point in the Middle Ages. One house I've done research on kept large numbers of medieval charters, but its archive has no medieval books. Another, in contrast, has many liturgical books and a few other devotional books still in its own archive. The dislocations of the 19th and 20th centuries might have caused books to be lost or destroyed, or moved into larger collections. Some translations of the Benedictine rule into Catalan might have been made for a women's monastery, for example. There is, I think, a lot that could be done on this topic, though I don't know if I am the right person to do it.

A parting note: a lengthy article on the Benedictine congregation in Catalonia indicated that copies of the orders constitutions were kept in the two largest nunneries associated with the congregation. Why them particularly? Is that somehow a testament to the quality of the nuns' libraries or record-keeping?

Apologies for the somewhat disconnected thoughts, I am still feeling my way on these questions.

Beguines in the NYT!

Meanwhile, I continue to slog through course materials. I am trying to select readings for the course I'll teach in the fall. I'll be starting a new visiting position, which means I don't yet have an office. This means that my academic books are crammed onto shelves, stacked into piles, and loaded into boxes, which are themselves stacked into piles. Finding a particular book I want to look at can require a lot of digging through boxes and stacks. This is just one of many things that are annoying about not having a permanent job.

I always find the process of selecting readings challenging--which selections to put together? is the reading too long? is the reading too short? etc. I know people in other disciplines who are able to simply pick a single textbook and use that for everything. I don't find that suitable for most of the courses I teach, and particularly not for something that is supposed to be a seminar. Getting the right balance of primary and secondary stuff, and making sure the reading load is challenging but manageable, is something I spend a lot of time, effort, and worry on.

Monday, July 14, 2008

Yes, nuns lived in monasteries

Meanwhile, I want to clarify a point of vocabulary regarding nuns, especially of the medieval variety.

It's customary in English to refer to houses of nuns as "convents" and houses of monks as "monasteries." This means that when I refer to "women's monasteries" I usually get some raised eyebrows. People have said to me, "Oh...they lived in monasteries?" sounding very impressed. Really, convents and monasteries are basically the same thing, it's simply a convention of English vocabulary, and I don't know when it developed. (Readers? any insights?)

I use the word monasteries to refer to women's communities because that's what my sources say. The Latin charters I'm dealing with refer quite consistently to a house for nuns as a monasterium. So they are clearly people who live in a monastery. The charters also use the word conventum. This word, in context, seems to refer to the religious community as a legal entity: the abbess and the conventum of the house together make decisions about buying and selling property, according to the charters, for example. Monasterium seems also to be used to refer to the physical building and its surroundings, but can also refer generally to the community. So these nuns (continental, not English) clearly lived in both a monastery and a convent, and I use both terms whenever they seem appropriate.

Friday, July 11, 2008

End of the week

I've been writing it in bits and pieces for the last few weeks, you see, so there's a substantial risk that I am repeating myself too much. Or not clarifying something enough, because I thought I had explained it earlier. I also need to think a bit about which journal I should send it to, and possibly revise it with that audience in mind.

Meanwhile, the Kalamazoo CFP is up, and I find myself uninspired. It would be nice to go to K'zoo next year, but I'm having trouble finding a session that seems well-suited to the things I'm working on. There seems to be a lot of lit stuff, which is not what I'm doing; there are some sessions on religious reform, which I might be able to do something with, but not much else that seems to link religion and gender. Or even to allow for the linkage of religion and gender; I can't very well submit a paper on nuns to a session that says it's about clergy, or mendicant preachers, or the like. I hate the feeling that I am trying to shoehorn my work into a slot that it really doesn't fit. I'll have to read through the CFP again, since I may be missing something, but on a first reading, my work seems like a difficult fit for any of the proposed sessions.

Monday, July 7, 2008

Jesus and his celestial harem?

It was common, in the Middle Ages, to describe nuns as brides of Christ. Consecrated virgins took Christ as their husband in lieu of an earthly husband. Much is made of this in any number of sources: one can find treatises discussing Jesus' superiority as a husband to any mere man and admonitions about how nuns must behave themselves lest they shame their "husband."

What becomes odd about this, to a modern reader, is how very literal much of the discussion of the motif is. Nuns are not merely metaphorical brides, but actual brides. The liturgy for consecrating a nun, for example, may contain direct references to the theme. The signature item of apparel for a nun was not so much her habit as her veil, an attribute of brides. When you look at the lives of individual holy women, you can find even more direct references: the ancient St. Katherine of Alexandria, according to her vita, received a ring; St. Catherine of Siena is among several holy women actually living in the Middle Ages who had similar visions of a ring and wedding ceremony. Special relationships with Christ, often accompanied by suggestive ecstasies, abound among female mystics. I have also found a text referring to Katherine of Alexandria's entrance into the celestial bedchamber. Medieval people were not just speaking poetically with this "bride of Christ" stuff; for many of them it appears to have been spiritual reality.

And where this gets even weirder...maybe even slightly disturbing...is when you reflect on the fact that Jesus was supposed to be married to all these nuns and saints at the same time. My current research has brought that home to me, as the texts shift back and forth between talking about a nun's individual relationship to Christ, as his bride, and talking about the nuns' spiritual endeavor as a collective. Such shifts seem a bit awkward, juxtaposing the spiritual reality of being a bride of Christ with the mundane reality of being a nun in a monastery together with many other nuns. How special could a nun feel about being Christ's bride when Sister Snoresalot, or Sister Condescending, in the next cell was also Christ's bride? The theme was widely used, for all sorts of purposes, and yet no one in the Middle Ages seems to have considered these implications.

Desk successfully excavated

The whole reason these files are on my desk is that I don't have enough space in drawers to file them properly. And no place to put a new filing cabinet, either, so that's out. This leads me to some questions:

- Do I really need to keep notes from classes I took as a student?

- What about notes I took during other people's talks?

- What about newsletters from various organizations I belong to?

More on nuns next post.

Thursday, July 3, 2008

Uh-oh

There's just one problem.

In order to write the next section, I have to excavate my desk.

I know that somewhere on my desk is a manila folder with printouts of the relevant documents I need to check before I can write this section. Somewhere, that is, under:

--book catalogs

--sample syllabi from my new employer

--notes I scribbled during sessions of the last two conferences I attended, one of which was in January

--random magazines

--mail I meant to deal with weeks ago

--photocopies of articles

--etc.

When my desk is organized, there are a lot of piles on it, but I know what type of thing is in each pile. When my desk is not organized, as now, everything smears into one big pile. So...time to go digging in the pile.

How is your desk organized (or not)?

Wednesday, July 2, 2008

When the writing is good

This project (the liturgy one) all along has nearly seemed to write itself. Despite that, it's been in progress for 2 years, interrupted by conference papers, a book manuscript, and job applications. From the beginning, when I was poring through the liturgical manuscripts, the basic idea came together very quickly. I wrote a sketchy introduction and a rough outline. How to organize a piece most effectively is often challenging for me, and this one fell into place very obviously: first I need to do this, then this, then that, then wrap up with this. I haven't had to seriously revise the structure of the essay at any point.

Writing is not always like this. In fact, this particular project is almost unique in my experience, in that it's been so easy to work with. Usually I do a lot more straining and revising and despairing over the utter crap I wrote the other day. But for now, the writing is good, and it feels wonderful. Hallelujah! I need to finish writing two short sections, do a pass through the footnotes and conclusion, and then it will be done! I almost hate to have to finish and send it off. The next project probably won't be nearly as easy.

Monday, June 30, 2008

Nuns on the run

Nuns were a pretty small portion of the documented runaways; a lot more were monks, canons, and friars. Sometimes nuns ran off with lovers; just as often they left their monasteries to attempt to claim inheritances. One of the things I really appreciated about this book is that nuns are fully represented in it. Many books about medieval monasticism treat nuns in a very cursory way, or leave them out entirely; Logan gives special attention to issues unique to nuns (pregnancy, for instance), but otherwise subjects them to the same analysis as monks. It's a pleasure to see such an evenhanded approach.

Thursday, June 26, 2008

Liturgy: not so scary

Why are they so nervous? Well, liturgiology (cool word, huh?) seems to be reputed as an especially esoteric part of the medieval studies field. There are, I suppose, some good reasons for this. Liturgical manuscripts are a distinct genre of manuscripts, with several different formal types. The manuscripts use a lot of jargon and abbreviations which have to be unravelled. Scholarship on liturgy also uses a lot of specialized vocabulary: can you tell Vespers from Matins? how about Lauds? what's the difference between an antiphon and a responsory? and so forth. Further, many liturgiologists (even cooler word!) work on very early liturgies, which involve even more specialized manuscripts, plus languages like Syriac, etc.

I'm not venturing into those waters. Instead, I'm working with late medieval liturgical manuscripts, which are safely in Latin. Once I've gotten a grip on the conventions of liturgical manuscripts generally--which is possible through a couple of excellent introductions--the manuscripts themselves are not that hard to work through.

Why put in the work? Because this is what nuns (and monks) did most of the day. Middle of the night, morning, scheduled intervals throughout the day, evening, the lives of people in monasteries were regulated by the liturgical routine. This is what they read, sang, heard, and experienced throughout their days. Liturgy had to have been crucial to how they understood themselves and the monastic life, and that's what I'm trying to uncover.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

Berks 2008

But what about the research, you ask? That was excellent, too. A session on "Gendering the Plague" showed how using the lens of gender helps wring new insights out of a very well-worn topic. A session on motherhood and nursing proved particularly lively, provoking a fascinating discussion on what medieval people thought made someone a "good mother" and various aspects of wet nursing.

For me, the highlight was the Sunday workshop with the lengthy title: "Using the Archives of Medieval Religious Women's Houses to Reflect on Their Secular Sisters." That's a mouthful. Though secular women were nominally the focus of these papers, many of them dealt with patronage of nuns, or cooperation between nuns and secular women. The ensuing discussion tended to come right back around to nuns, as one participant remarked.

Unfortunately, the papers are no longer available from the Berks website. Here are some of the common themes from the papers and the discussion:

- The boundary between "religious woman" and "secular woman" is quite porous

- Women of high, middling, and low status all had connections to nunneries

- There is still a lot we don't know about how and why medieval women became nuns

- There is still a lot we don't know about how and why lay people supported nuns

Why a blog?

I am now several years past that dissertation. While I shop around a book manuscript, I'm attempting to work on other projects. I've got at least three separate essays I'd like to work on this summer. More about those in future posts.

So here are my current intentions for this blog:

I will endeavor to post regularly.

I welcome comments, and I will try to respond to them regularly. But:

I will delete spam, personal attacks, and other obnoxious comments.